Where Rome Came to Wash, Talk, and Think

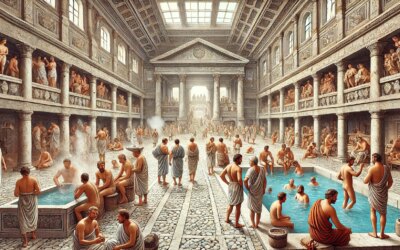

Steam rises through vaulted halls, echoing with laughter, conversation, and the splash of water. Citizens of every social class relax on marble benches, plunge into cold pools, or sweat in dry heat. Slaves carry oils and towels; merchants discuss business while scribes take notes. This is a Roman bathhouse—thermae—in the 1st century AD: a microcosm of Roman society where hygiene, leisure, and public life converged.

The Birth of Public Bathing Culture

While simple bathhouses existed in early Rome, the grandeur of the imperial thermae blossomed under emperors like Agrippa, Nero, and later Titus and Trajan. By the 1st century AD, bathing had become a daily ritual and civic institution, accessible to nearly all free citizens.

Baths were not just about cleanliness—they were centers of physical, intellectual, and social activity. Visiting the baths was as routine as going to the market or the forum.

Architecture of Leisure

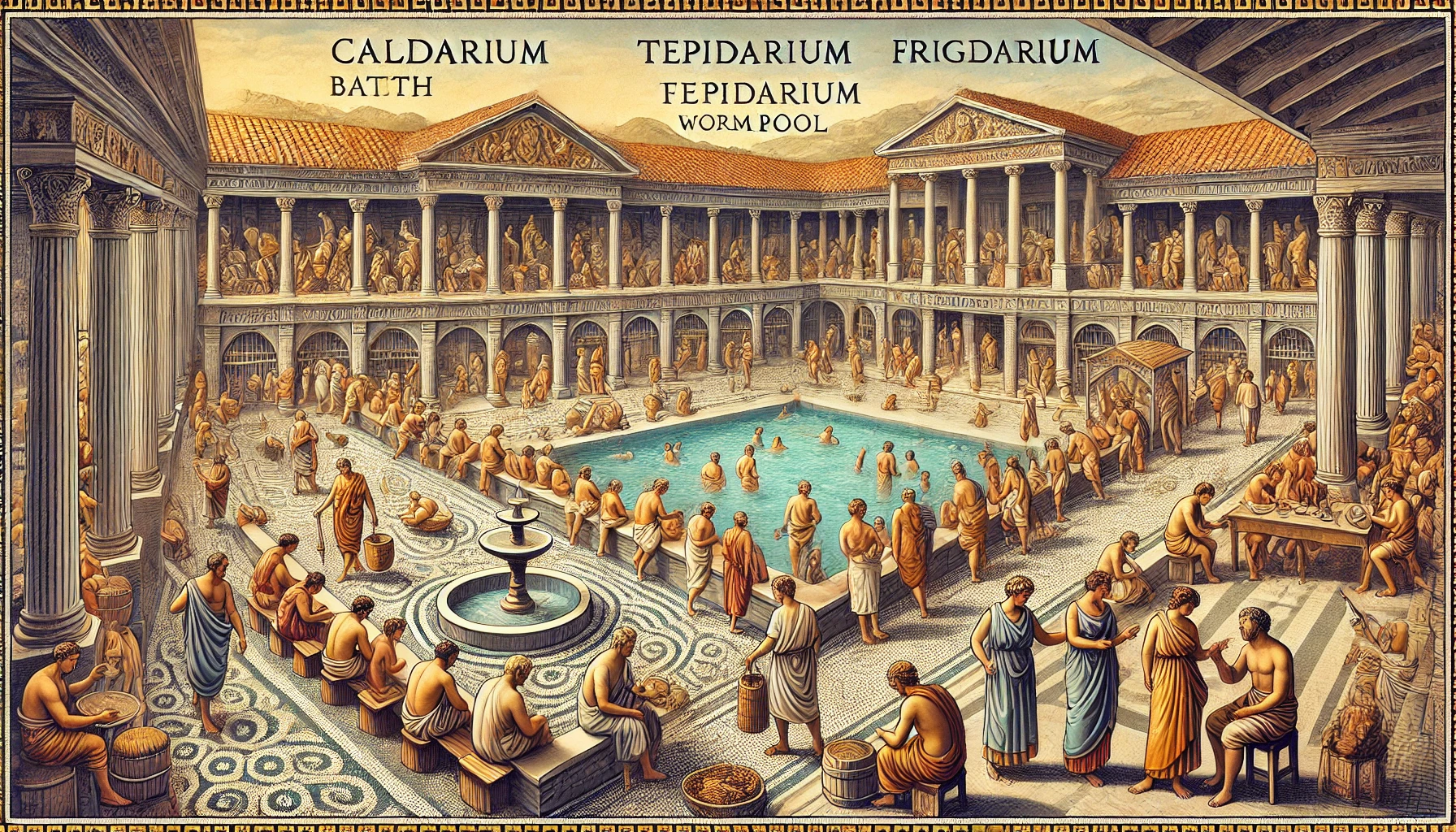

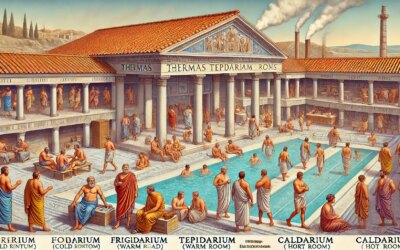

Thermae were vast, complex structures, often financed by wealthy patrons or the emperor himself. Key components included:

- Apodyterium – The changing room, with niches for clothes and attendants for valuables

- Tepidarium – A warm room to acclimate the body and promote relaxation

- Caldarium – The hot bath room, with heated pools and steam generated by the hypocaust system beneath the floors

- Frigidarium – A cold plunge pool to invigorate after heat

- Natatio – A large open-air swimming pool

Surrounding these were gardens, gymnasiums, libraries, snack bars, and even lecture halls. The best baths, like the Baths of Agrippa, were works of art—lined with mosaics, frescoes, and sculptural decoration.

The Hypocaust: A Revolution in Heating

Rome’s engineers devised the hypocaust, a central heating system that circulated hot air beneath raised floors and through wall flues. This allowed the caldarium and tepidarium to remain warm year-round.

Furnaces (praefurnia) stoked with wood kept air flowing, with slave labor maintaining temperature and fuel supply. The result was a technological marvel unmatched in the ancient world until the modern age.

Who Bathed in Rome?

Baths were public and inclusive. Entry fees were minimal, and often waived by the state. Men and women bathed separately—either at different times or in different wings. Elite families, merchants, soldiers, and laborers alike mingled within the same walls.

Children learned to swim here; philosophers debated; politicians canvassed for support. Only slaves and the very poor were excluded, though some accompanied their masters or worked as attendants within the baths.

The Ritual of Bathing

Bathing was a multi-stage affair often lasting hours:

- Visitors changed in the apodyterium

- Warmed themselves in the tepidarium

- Sweated and soaked in the caldarium

- Were scrubbed with strigils and oiled by slaves

- Plunged into the frigidarium for a bracing finish

Many also stopped at the palaestra (gym) for exercise or joined friends for food and drink. Baths offered the ultimate blend of hygiene and hedonism.

Social and Political Life

Thermae were places of networking and negotiation. Senators discussed policy, merchants forged deals, poets recited verses. Bathhouses were equalizers, where citizens interacted across class boundaries—yet subtly reinforced hierarchy through behavior, dress, and conversation.

The presence of statues of emperors and gods reminded bathers that cleanliness was next to Romanitas—an expression of civilization and imperial grandeur.

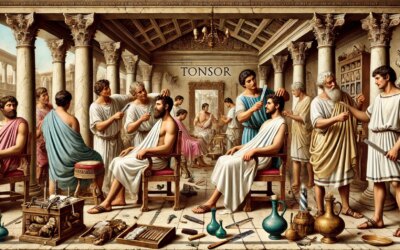

Entertainment and Amenities

Many baths offered:

- Food vendors and drink sellers

- Barbers and masseurs

- Libraries with scrolls and seating

- Music and games—sometimes even theatrical performances

Public readings and philosophical debates were common, especially in the baths near intellectual hubs like the Palatine Hill or Campus Martius.

Women and the Baths

While less documented, women frequented baths, often in the morning before men’s hours. Female-only baths (balnea muliebria) existed, though mixed bathing (co-ed) occurred during the empire’s more permissive periods.

Women’s bathing rituals included beauty treatments, socializing, and religious observances, with their own attendants and spaces for rest and care.

Legacy of the Roman Thermae

After the fall of the Western Empire, many baths fell into disrepair, but their influence endured. The Islamic hammam and European bathhouses drew heavily on Roman design. Modern spas and wellness centers echo the communal, therapeutic vision of the thermae.

Roman bathhouses remain among the most iconic and enduring symbols of ancient daily life, engineering, and urban planning.

In Steam, Civilization

To walk through a Roman bath was to immerse oneself in the essence of the empire. Equal parts public utility and cultural theatre, the thermae offered more than hot water—they offered health, connection, and continuity in a world perpetually in motion. As the steam rises, so too does the spirit of Rome—warm, communal, and enduring.