The Roots of Roman Learning

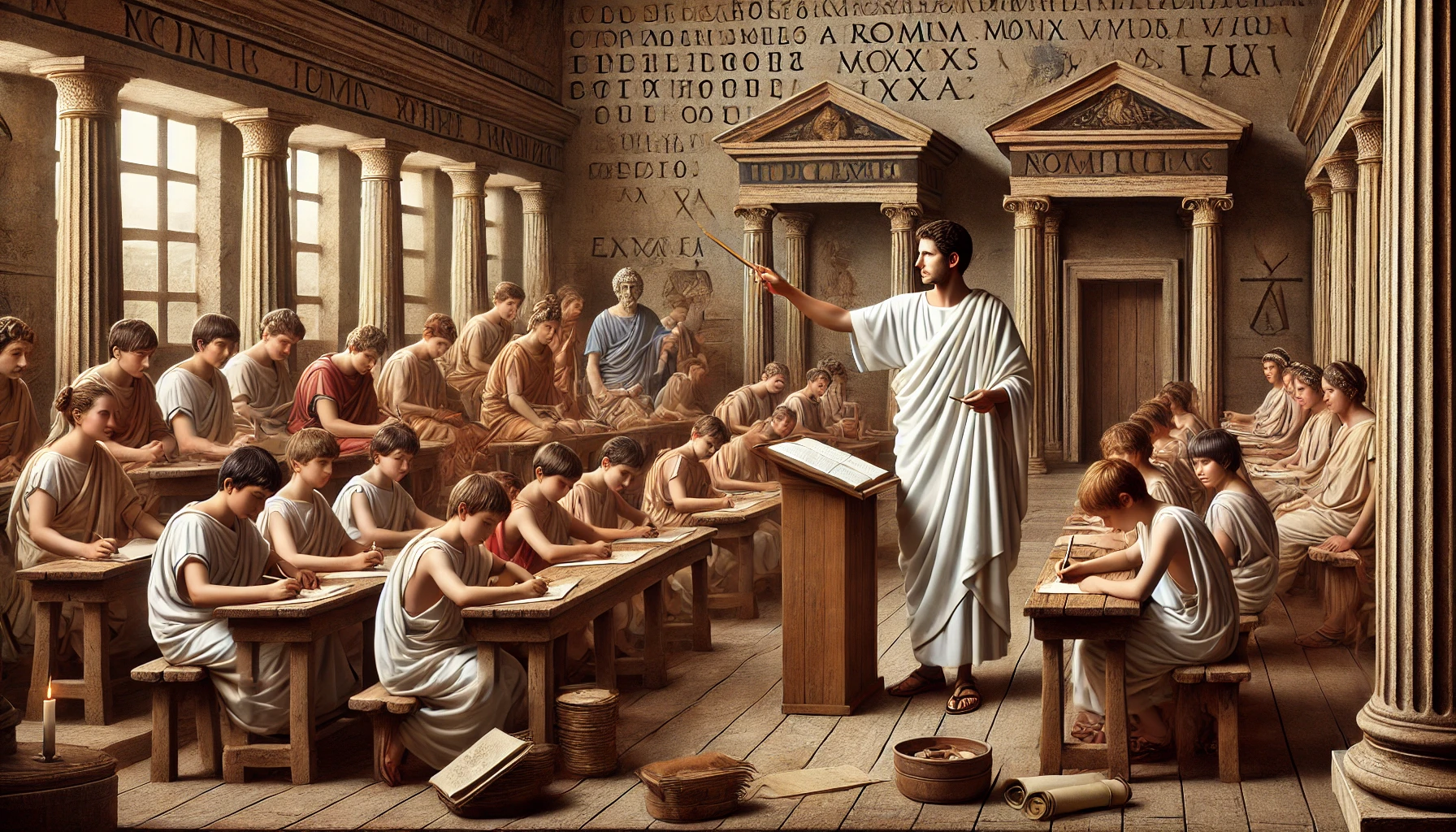

In the heart of a Roman provincial town or city, the sound of recitation echoes off painted walls and marble columns. A teacher in a toga walks between rows of wooden benches as young boys scribble on wax tablets or recite passages from Virgil. This is a Roman classroom in the 2nd century AD—a place where rhetoric met discipline, and the foundations of civic life were laid.

Who Went to School in Ancient Rome?

Roman education was primarily for freeborn boys of citizen families, although some girls—especially in wealthy households—received private instruction. Education began at home in early childhood, with parents or tutors introducing basic literacy. Around age seven, boys might attend a public school run by a ludi magister, or remain under the tutelage of a private tutor, often a Greek slave or freedman.

Attendance and quality varied by wealth, location, and social status. The children of senators and equites had access to top-tier instructors, while plebeian families made do with modest schools or home-based learning. Education was both a privilege and a tool of social mobility.

The Roman Curriculum: What Was Taught?

Roman education followed a three-tiered system:

- Ludus litterarius – Basic literacy and numeracy, including the alphabet, syllables, and simple arithmetic. Pupils used wax tablets and styluses to practice writing.

- Grammaticus – Literary education in Latin and Greek texts. Students studied poetry (especially Homer and Virgil), mythology, history, and grammar.

- Rhetor – Advanced studies in rhetoric, argumentation, and oratory. This stage prepared elite youths for careers in law, politics, or public service.

Lessons emphasized memorization, repetition, and moral instruction. Students learned through reading aloud, copying texts, and debating topics of civic or philosophical importance. Physical punishment for mistakes was not uncommon.

The Role of the Teacher

The teacher’s role was both educational and disciplinary. A magister was expected to be learned, firm, and capable of molding young minds into articulate citizens. Status varied—some teachers were slaves or freedmen, others were respected intellectuals or philosophers.

Famous educators, like Quintilian, left behind treatises on pedagogy that influenced Roman and later European thought. His work, *Institutio Oratoria*, advocated for compassionate teaching and emphasized the development of character alongside intellect.

Tools and Materials in the Classroom

Roman classrooms were modest by modern standards but equipped with functional materials:

- Wax tablets and styluses – Reusable for writing exercises.

- Papyrus scrolls – For more permanent reading and copying.

- Abacus – Used to teach arithmetic through counters and grooves.

- Inkwells and quills – For students practicing more advanced writing.

Classrooms might be held in open courtyards, colonnaded porticos, or even rented rooms within larger homes. The environment could be noisy and austere, but the focus on verbal learning made it dynamic and interactive.

Discipline and Classroom Culture

Roman education was rigorous and often strict. Discipline was enforced through corporal punishment, ridicule, and competition. Students were expected to stand, speak loudly and clearly, and memorize long passages. Success brought praise and prestige; failure invited shame and correction.

Despite the harshness, many pupils developed a deep love for learning. Education offered the keys to literary fame, civic responsibility, and imperial service. For Rome, literacy and eloquence were markers of culture and power.

Education Beyond the Classroom

Learning continued outside formal settings. Children learned trades from parents, religious traditions from priests, and philosophy from private tutors or traveling speakers. Wealthy families cultivated libraries, hired Greek scholars, and sent sons to Athens or Alexandria for higher education.

Public speeches, theatrical performances, and forums also served as spaces of informal education, exposing youth to ideas, rhetoric, and civic discourse.

The Role of Girls in Education

Though often overlooked, girls in affluent families did receive education, especially in reading, writing, and music. Some were taught Greek and Latin literature, household management, and moral philosophy. Educated women like Cornelia (mother of the Gracchi) and Julia Domna (wife of Septimius Severus) played influential roles in Roman society and letters.

However, most Roman girls were trained for domestic life and rarely attended formal schools. Their education was guided by mothers, nurses, and private tutors within the home.

Legacy and Influence

Roman education laid the foundation for Western pedagogical tradition. Its focus on rhetoric, classical texts, and civic identity echoed through medieval scholasticism, Renaissance humanism, and even modern liberal arts curricula.

Today, schools still use many Roman concepts—curricula, classrooms, exams, and public speaking—all evolved from the educational ideals shaped in 2nd-century Rome.

Shaping Minds, Shaping Rome

The Roman classroom was a microcosm of the empire itself—ordered, disciplined, ambitious. It turned boys into senators, lawyers, and poets; it taught values, language, and power. Though centuries have passed, the voices once raised in Roman classrooms still echo in every school bell, every debate, and every written word inspired by ancient learning.