Rome’s Hidden River of Stone

Long before aqueducts spanned valleys and monumental temples crowned the Forum, the early Romans undertook a feat of engineering that would anchor their city’s rise: the construction of the Cloaca Maxima. Begun in the 6th century BCE, this massive underground sewer was one of the first examples of large-scale public infrastructure in Western civilization. Its enduring legacy flows silently beneath Rome to this day—testament to the ingenuity of a civilization just emerging from myth into history.

From Marshland to Cityscape

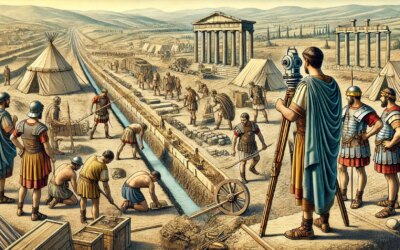

According to tradition, the Cloaca Maxima was initiated under the reign of Rome’s fifth king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (r. 616–579 BCE), and continued under Tarquinius Superbus, the last of the kings. The area that would become the Roman Forum was originally a marshy lowland between the Capitoline and Palatine hills. Seasonal flooding from the Tiber created stagnant pools and foul smells, impeding early urban development.

To transform this inhospitable ground into usable land, the Romans needed a system to drain excess water and manage waste. The solution was bold: a vaulted channel carved into the earth to collect and redirect runoff and sewage into the Tiber. This project not only enabled the Forum’s creation—it set the precedent for Roman civil engineering for centuries to come.

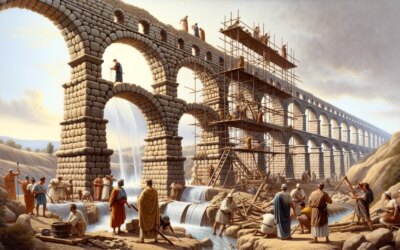

The Structure and Evolution of the Sewer

The Cloaca Maxima began as an open-air canal, lined with stone blocks and gradually covered over as urbanization increased. Eventually it became a fully enclosed tunnel—wide enough for a person to walk upright or even navigate by small boat during maintenance. The earliest portions were built using large, fitted tufa blocks and mortarless masonry, a technique borrowed from Etruscan predecessors.

The sewer’s main artery ran beneath the Forum and into the Tiber, collecting water from tributaries, springs, and waste from private homes and public buildings. Smaller drains fed into the main cloaca, forming a rudimentary but effective sanitation network. Over time, the system expanded to include additional branches and intakes, adapting as Rome’s population swelled.

Function and Urban Impact

While primarily a drainage canal, the Cloaca Maxima also served as a sanitation channel—helping prevent the spread of disease by flushing away sewage. Its influence was immense. The ability to build atop previously unusable land made possible the Forum Romanum, the political and religious heart of the city. Temples, basilicas, markets, and courts soon rose above ground while water flowed unseen below.

Public latrines, bathhouses, and fountains all eventually fed into the system, reflecting Rome’s commitment to hygiene and urban organization. The concept of central waste removal was far ahead of its time, unmatched in much of Europe until modernity.

Maintenance and Engineering Culture

Though begun under the monarchy, the sewer was maintained and improved throughout the Republic and Empire. Engineers regularly inspected and repaired it—testifying to the Romans’ long-term investment in infrastructure. Pliny the Elder marveled at the Cloaca Maxima in his Natural History, praising how it remained functional centuries after its construction despite floods and time.

Roman engineers, known for their practical expertise, incorporated the Cloaca into broader water management systems. As aqueducts brought clean water in, the Cloaca took waste out—a full cycle of urban hydraulic design.

Symbolism and Sanctity

The Cloaca Maxima was more than a utility—it held symbolic and religious significance. Romans regarded it as a sacred achievement, a sign of their mastery over nature and chaos. The goddess Cloacina was even venerated as the sewer’s divine protector. A small shrine—Sacrum Cloacinae—once stood above a main access point near the Forum.

Its sacredness was also practical: treating infrastructure with reverence ensured it received due care. The blending of the spiritual with the civic defined Roman attitudes toward many public works.

Legacy Beneath the Stones

Today, portions of the Cloaca Maxima remain in use, integrated into Rome’s modern sewer system. Archaeologists and engineers continue to study its construction, marveling at how a project begun nearly 2,600 years ago still survives. Tourists can view its outflow near the Ponte Rotto on the Tiber’s banks—a silent testament to the foresight of early Roman planners.

The Cloaca Maxima laid the foundation for Roman engineering’s golden age. It proved that civil infrastructure could not only solve immediate problems but enable future greatness. Beneath the marble and monuments of Rome lies a hidden masterpiece—one that made them possible in the first place.