Storm Over Britannia: Setting the Stage

In the year 367 AD, the western Roman Empire faced one of its most severe regional crises: a near-total collapse of control in the province of Britannia. Known to history as the Great Conspiracy, this coordinated uprising involved native Britons, Picts from the north, Irish raiders (Scotti), and Saxon pirates from across the sea. It struck while the imperial military was overstretched and politically fragile, exposing the vulnerabilities of Rome’s frontier defenses during the late empire. The crisis would demand a swift and brutal response—one orchestrated by Emperor Valentinian I and his top generals, including Count Theodosius, father of the future emperor Theodosius I.

The Collapse: How Britannia Fell into Chaos

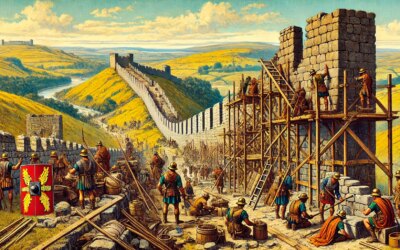

The Roman occupation of Britain, dating back to 43 AD, had gradually eroded by the late 4th century. By the 360s, frontier garrisons along Hadrian’s Wall and coastal fortifications—collectively known as the Saxon Shore—were undermanned and underfunded. In early 367 AD, multiple enemy groups launched near-simultaneous attacks. The Picts broke through the northern frontier, the Scotti raided from Ireland, and the Saxons struck from the eastern coast. Internal rebellions and desertions by the limitanei (frontier troops) compounded the chaos.

The situation escalated when the Roman military commander of Britain, Fullofaudes, disappeared—either captured or killed. The provincial governor, Nectaridus, was reportedly slain during the initial invasions. The sudden loss of leadership left the island paralyzed. Cities were plundered, Roman villas burned, and trade collapsed. For several months, Britain was effectively severed from Roman rule.

Emperor Valentinian I’s Response

Valentinian I, an experienced general known for his defensive policies, reacted decisively. From his base in Gaul, he dispatched Count Theodosius in late 367 with a specialized task force. Theodosius was a veteran of campaigns in Africa and Gaul, chosen for his logistical skill and unyielding discipline. He arrived in Britain in early 368 with a fleet of supply ships and elite troops, including units of the Comitatenses (field army).

The Reconquest: Military Operations and Reforms

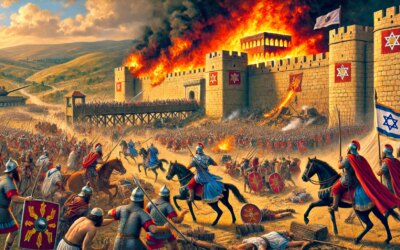

Once in Britannia, Theodosius executed a rapid counteroffensive. He first secured the southeastern ports, reestablishing supply chains and rallying surviving Roman forces. His troops then moved northward, systematically retaking towns and fortresses. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, Theodosius “restored peace by strength, not negotiation.” By autumn 368, major enemy forces had been driven out, and punitive raids were launched across the Irish Sea and into Pictish territories.

Beyond military success, Theodosius restructured provincial administration. He created a new military command, the Dux Britanniarum, and fortified urban centers. To prevent future conspiracies, a thorough purge was conducted among collaborating Britons and negligent officers. Ammianus writes that “traitors were rooted out with fire and sword.” These actions reestablished Roman authority—but also signaled that the empire’s grip was weakening.

The Strategic Significance of the Crisis

The Great Conspiracy marked a turning point. Though Britannia was retaken, the episode exposed the deep structural weaknesses of late Roman administration. Troops had to be recalled from the continent, weakening defenses elsewhere. Moreover, the empire’s reliance on rapid-response generals like Theodosius underscored how reactive, not proactive, Rome had become. Valentinian’s personal inspection of the Rhine defenses in 368–369 (possibly visiting the Channel region) reflects the emperor’s concern about wider instability.

Long-Term Effects and the Fate of Roman Britain

Though Roman rule in Britain continued for another four decades, the Great Conspiracy foreshadowed its eventual collapse. The repairs initiated by Theodosius could not reverse the trend of decentralization and weakening military morale. By 410 AD, Rome formally abandoned Britain, and the island fragmented into competing post-Roman kingdoms.

Nevertheless, the 367–368 reconquest temporarily reaffirmed Rome’s resolve and capability. Theodosius was later rewarded with high honors, and his son, Theodosius I, would rise to rule the empire. But the memory of Britain nearly lost served as a warning: even the most secure provinces were vulnerable if left neglected.

A Lesson in Resilience and Limits

The Great Conspiracy stands as a vivid reminder of Rome’s dual nature in the late empire—its capacity to recover under pressure, and its chronic exposure to internal decay and external threats. In responding with force and reform, Valentinian and Theodosius demonstrated that imperial discipline could still prevail. Yet the cracks were widening, and Britain’s brush with collapse was a prelude to the empire’s unraveling decades later.