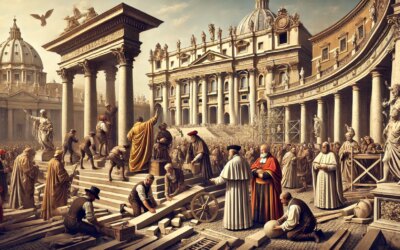

Introduction: Resolving a Century-Old Conflict

On February 11, 1929, a historic accord was signed within the walls of Rome’s Lateran Palace. Known as the Lateran Treaty, this agreement between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See resolved the “Roman Question” that had plagued Italian politics since the unification of Italy in 1870. It recognized the Vatican as an independent sovereign state and established a new relationship between the Catholic Church and the Italian government.

The Roman Question: A Nation Divided

Since the capture of Rome by Italian forces in 1870, the Papacy had refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Italian state’s authority over the former Papal States. Popes considered themselves “prisoners” within the Vatican, refusing to leave its confines in protest. The standoff fostered political instability and divided Italian society, where loyalty to the Pope often conflicted with loyalty to the secular state.

Negotiations and the Key Figures

In the late 1920s, Italy’s Fascist regime, under Benito Mussolini, sought to resolve the impasse to consolidate national unity and strengthen its political legitimacy. On the Church’s side, Pope Pius XI, aided by Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri, was eager to restore the Church’s autonomy and influence. After months of delicate negotiations, the two parties reached an agreement that balanced political pragmatism with religious demands.

The Terms of the Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty consisted of three agreements:

- The Treaty: It recognized Vatican City as an independent sovereign entity, granting the Pope full political control over the territory.

- The Concordat: It defined the relationship between the Italian state and the Catholic Church, ensuring privileges for Catholicism in Italy, such as its recognition as the state religion and the regulation of religious marriage.

- The Financial Convention: It provided the Church with compensation for the loss of the Papal States, amounting to 750 million lire and a considerable amount of Italian government bonds.

Impact on Italy and the Church

For Mussolini, the treaty was a political triumph, bolstering his domestic standing and presenting Fascism as a unifying force for the nation. For the Catholic Church, it marked the end of the self-imposed isolation and restored its ability to influence both Italian and international affairs. The Church, while gaining independence, also re-established its presence as a moral and political authority in Italy.

The Birth of Vatican City

Vatican City, covering just 44 hectares, became the world’s smallest independent state. It possessed its own governance structures, postal system, and even a small military contingent—the Swiss Guard. More importantly, it provided the Pope with a secure and sovereign base from which to exercise global spiritual leadership, free from external political pressures.

Legacy of the Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty has had enduring consequences. It stabilized Church-state relations in Italy and provided a model for modern agreements between religious institutions and secular governments. Though modified over the decades, especially after the Second Vatican Council and the revision of the Concordat in 1984, the Lateran Treaty’s core principles still shape the existence of Vatican City today.

Conclusion: A Milestone in Modern History

The signing of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 closed a turbulent chapter of Italian history and gave birth to a unique entity at the heart of Rome. By resolving an intractable political-religious conflict, the treaty allowed both the Church and the Italian state to move forward—separately yet side by side—into the complexities of the 20th century and beyond.