Women of Status in a Shifting Empire

By the 4th century AD, the Roman Empire was undergoing profound transformation—Christianity was becoming state religion, military leadership often determined imperial succession, and economic structures were evolving under pressure. Yet in the midst of these shifts, Roman noblewomen retained and even expanded their influence, particularly in family estates and private social networks. In the richly frescoed atria of Roman villas, women shaped the moral, educational, and political tone of elite society—quietly but decisively.

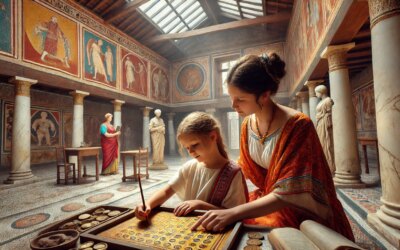

Education and Literacy: The Rise of the Cultivated Matron

Wealthy Roman women in Late Antiquity were often educated in literature, philosophy, and scripture—especially after Constantine’s embrace of Christianity in the early 4th century. Figures like Melania the Younger and Proba Falconia were known for their Latin poetry and religious scholarship. In villa atriums, noblewomen supervised their children’s tutors, read aloud from the works of Cicero or the Gospels, and corresponded with churchmen and politicians.

Wax tablets, styluses, and scrolls were part of everyday life in the elite household. Women kept detailed financial accounts and managed large estates in the absence or disinterest of their husbands. Literary salons, hosted in Roman villas, became places where aristocratic women directed the tone of cultural life.

Household Power and Matrimonial Politics

Marriage remained central to a noblewoman’s social role. Unions between aristocratic families were tools of political alliance, often negotiated from a young age. A matron could wield influence not only through her birth family, but also by arranging advantageous matches for her children and maintaining diplomatic relations across extended kinship networks.

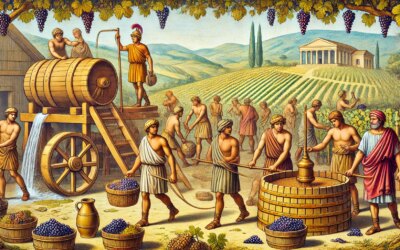

While the *paterfamilias* still held legal authority, noblewomen such as Galla Placidia—daughter of Emperor Theodosius I and later regent for Valentinian III—demonstrated that women could hold real political agency, especially in times of crisis. Even in less visible roles, women managed household slaves, oversaw agricultural production, and ensured family rituals were properly observed.

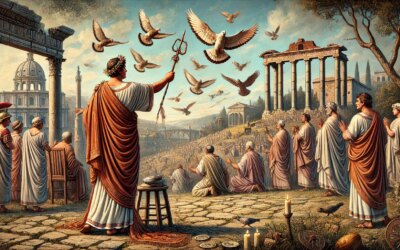

Faith and Philanthropy in a Christianized Rome

As Christianity spread, elite women became key supporters of the Church. Many turned their villas into sites of charitable outreach, hosting orphans, founding monasteries, and endowing basilicas. Melania the Elder gave away vast wealth to support pilgrimages, monasteries, and the poor. Christian ethics increasingly shaped elite female conduct—chastity, modesty, and piety were extolled alongside traditional Roman virtues like pietas and dignitas.

This new religious patronage reshaped public roles. Noblewomen appeared less in civic processions or temple rites, but more often in religious foundations, often as deaconesses, patrons, or widowed benefactors. Tomb inscriptions celebrated both moral virtue and acts of charity, blending Roman and Christian ideals.

Fashion, Identity, and Symbolic Authority

Clothing in the 4th century remained a marker of social class and identity. Elite women wore stolae of fine wool or silk, often dyed purple or embroidered with gold thread. The palla, a cloak-like shawl, was draped elegantly during public appearances. Jewelry—gold earrings, gemstone rings, and elaborate necklaces—projected wealth and status, but increasingly carried Christian symbolism like the Chi-Rho or dove.

Hairstyles became simpler compared to the flamboyant coils of earlier imperial periods, reflecting a move toward Christian modesty. Yet portrait busts and mosaics from the period still show deliberate attention to appearance and social presentation.

Living Spaces as Social Arenas

The Roman villa in Late Antiquity was not just a residence—it was a stage for influence. The atrium functioned as a reception space, a domestic chapel, and a symbol of lineage. Wealthy women managed these settings with precision, curating art collections, commissioning mosaics, and displaying family ancestors in painted panels or sculpted busts.

Here, guests were entertained, alliances were nurtured, and decisions were quietly orchestrated. The inner rooms housed looms, libraries, and letter-writing tables—domains where elite women shaped culture and legacy.

Echoes Through Time

Though Roman noblewomen of the 4th century AD rarely left direct records, their influence reverberates through architecture, art, and law. The Christian matron became an ideal that survived into Byzantine and medieval models of queenship and noblewomanhood. Their education, estate management, and moral authority set the tone for centuries of female aristocratic roles to follow.

Behind the decorated walls of their villas, these women helped preserve Roman civilization during its transformation. They deserve to be remembered not as shadows in men’s biographies, but as architects of continuity in an age of change.