A Stage for the People: The Role of Theater in Roman Society

In the bustling cities of the Roman Empire, public entertainment was as essential to civic life as baths, markets, and temples. Among the most popular forms of leisure was the theater, where citizens of all classes gathered to watch performances that ranged from slapstick comedies to tragic dramas and political satire. Unlike the gladiatorial games or chariot races, Roman theater offered a more cerebral, albeit often bawdy, form of entertainment. It was also a platform for social commentary, subtly challenging norms and lampooning elites.

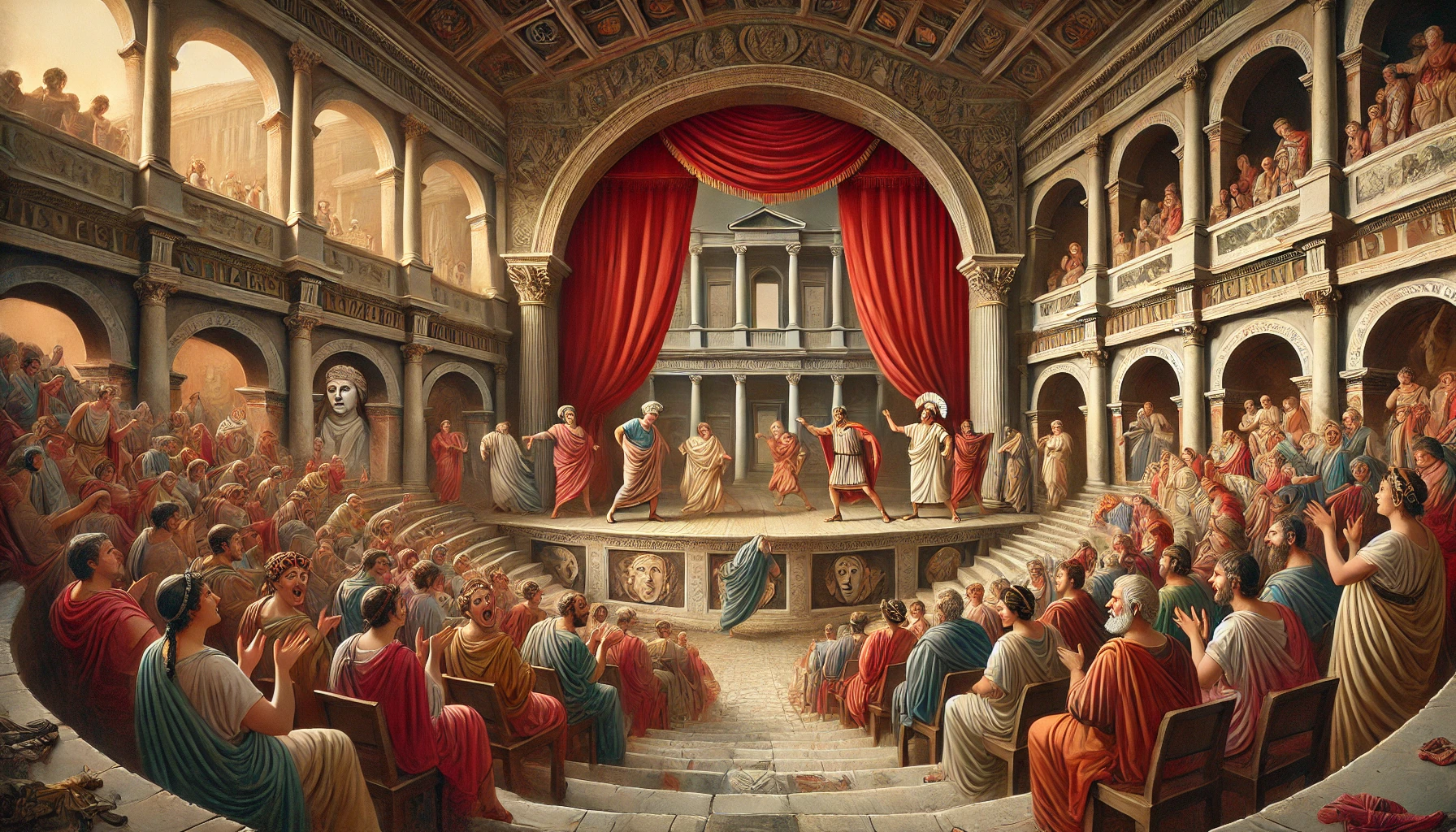

The Architecture of Spectacle

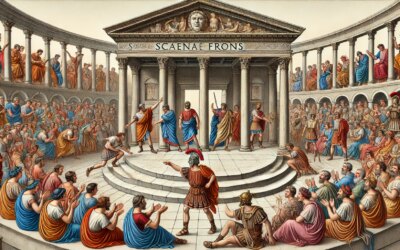

Roman theaters were architectural marvels, often inspired by Greek predecessors but adapted for Roman urban needs. Constructed with semicircular seating (cavea), elevated stages (pulpitum), and elaborate backdrops (scaenae frons), they were built into hillsides or free-standing with concrete vaulting. The Theater of Marcellus in Rome, inaugurated around 13 BC, is a prime example—seating up to 20,000 spectators with arcaded tiers and excellent acoustics.

Unlike Greek theaters, which were typically open-air, some Roman versions used retractable awnings (velarium) to shade the audience. Theaters were located in cities across the empire—from Orange in Gaul to Bosra in Syria—testifying to their popularity and standardization under imperial influence.

Genres on Stage: From Farce to Philosophy

Comedy and the Masks of Laughter

Roman comedies, modeled on Greek New Comedy, flourished through playwrights like Plautus and Terence. These performances featured stock characters: the braggart soldier (miles gloriosus), the cunning slave (servus callidus), and the miserly father (senex). Performers wore exaggerated masks to signal character types and emotions, aiding visibility in large venues. Humor often revolved around mistaken identities, sexual innuendo, and social satire—a safe way to critique Roman society under the guise of farce.

Tragedy and Moral Reflection

Though less popular than comedy, Roman tragedy, particularly in the works of Seneca, offered moral and philosophical exploration. These dramas dealt with revenge, fate, and the flaws of power. Performed with heightened emotion and stylized gestures, they appealed to the elite and reflected Stoic themes of duty and suffering. Tragically, few full Roman tragedies survive, but their influence endures through Renaissance revivals of Senecan drama.

Behind the Curtain: The World of Performers

Actors (histriones) in Rome occupied a low social status, often drawn from freedmen or enslaved backgrounds. Despite this, star performers could earn fame and patronage. Troupes were usually managed by producers (domini gregis), and scripts were memorized and delivered in highly codified physical language. Female roles were typically played by men, though in later imperial periods some women did perform, especially in mime and pantomime genres.

Beyond the Stage: Mime, Pantomime, and Politics

Aside from traditional drama, mime and pantomime gained immense popularity. Mime was ribald and often improvised, portraying everyday life with humor and lewdness. Pantomime, a solo dance-drama without spoken words, conveyed myths through elaborate gesture and music, captivating audiences of all classes.

Theater also carried political undertones. Satirical performances could mask critiques of emperors and magistrates. Augustus and Nero both sponsored theater extensively but also censored scripts and performances that crossed boundaries. As such, theater served both as a tool of imperial propaganda and a vehicle for veiled dissent.

Audiences and Experience

Roman theaters were open to the public and typically free of charge, thanks to wealthy sponsors or the state. Seating was stratified: senators sat closest to the stage, while women, slaves, and the poor were relegated to upper tiers. Crowds were loud, opinionated, and deeply involved—applauding, booing, and sometimes even pelting poor performers with fruit.

Festivals like the Ludi Romani and Ludi Megalenses featured extensive theatrical programs. Some lasted for days, with interludes of music, dance, and even mock battles, turning the theater into a hub of cultural and civic life.

Theater’s Enduring Footprint

While Roman theater declined in the Late Empire—overshadowed by Christian disapproval and shifting tastes—its legacy persisted. Many Western theatrical traditions, from commedia dell’arte to Elizabethan drama, owe much to Roman models. The use of stock characters, narrative structure, and even the architectural design of modern theaters reflect ancient innovations.

A Cultural Forum in Every City

The Roman theater was more than a venue for entertainment—it was a forum for ideas, emotion, and community. From the laugh of a plebeian in the back row to the approving nod of a senator in the front, the theater reflected and shaped the Roman world. In stone arches and surviving scripts, its voice still echoes through time.