Introduction: Seeking Peace in a Century of War

Signed on May 8, 1360, the Treaty of Brétigny was a major attempt to bring an end to the brutal early phase of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. Though it offered temporary respite, the treaty ultimately failed to deliver lasting peace, illustrating the deep-rooted tensions that would keep Europe embroiled in conflict for decades to come.

Background: Decades of Conflict

The Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) erupted from dynastic disputes over the French throne, complicated by economic rivalry and feudal loyalties. Following devastating battles such as Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356), where the English forces, led by Edward the Black Prince, captured the French King John II, the French monarchy was severely weakened. Negotiations became inevitable as both sides sought to recover and regroup.

The Terms of the Treaty

The Treaty of Brétigny was notable for several key provisions:

- Territorial Concessions: France ceded extensive territories in Aquitaine and other regions to England, greatly expanding English holdings in southwestern France.

- Ransom of the French King: King John II would be released from English captivity upon the payment of an enormous ransom of three million écus.

- Renunciation of Claims: Edward III of England renounced his claim to the French throne in exchange for full sovereignty over his new possessions, though the sincerity of this renunciation was later questioned.

- End of Allegiances: Vassals in the transferred territories were no longer considered subjects of the French crown.

The Ceremony at Brétigny

Negotiations culminated at the small village of Brétigny, near Chartres. The atmosphere was tense, with both sides wary of betrayals. Formal ceremonies sealed the agreement, with solemn oaths taken under the gaze of church officials and knights. Despite the pomp, many contemporaries doubted the durability of the accords.

The Fragility of Peace

While the treaty brought a few years of relative quiet, it planted seeds of future discord. The financial strain of paying King John II’s ransom devastated the French economy, leading to internal unrest. Meanwhile, England struggled to maintain control over its expanded territories. Mutual distrust persisted, and neither monarchy fully relinquished its ultimate ambitions, setting the stage for renewed warfare.

The Resumption of Hostilities

By the late 1360s, tensions flared anew. French forces, under King Charles V, launched campaigns to reclaim lost lands, effectively undoing many of Brétigny’s terms. The war evolved into a prolonged, grinding conflict that would shape the fate of both nations and the wider European political landscape.

Legacy of the Treaty of Brétigny

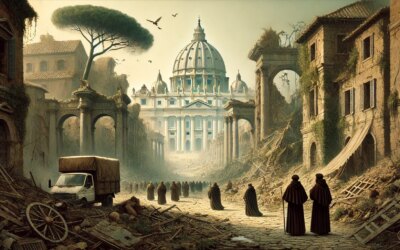

Though ultimately unsuccessful in securing lasting peace, the Treaty of Brétigny remains a landmark in the history of diplomacy during the Middle Ages. It highlighted both the potential and the limits of negotiation in an age dominated by dynastic ambition and military power. The treaty also underscored the human cost of war, with entire regions left devastated by shifting allegiances and incessant conflict.

Conclusion: A Momentary Pause in a Long War

The Treaty of Brétigny was a fleeting moment of hope amid a century of devastation. It serves as a poignant reminder of how difficult it is to resolve deep-rooted rivalries and how, in medieval Europe, peace was often just a prelude to further strife. In the grand sweep of the Hundred Years’ War, Brétigny was both a diplomatic achievement and a tragic missed opportunity for lasting reconciliation.