Introduction: Empire Meets Resistance

In the summer of 70 AD, one of antiquity’s most defining conflicts reached its climax. The Roman general Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, led legions against the Jewish rebels holding Jerusalem. The ensuing siege would result in the destruction of the Second Temple—an act that not only crushed the Great Jewish Revolt but echoed across centuries of faith, politics, and memory. For Rome, it was a display of imperial power. For the Jewish people, it was a trauma of unimaginable depth.

The Great Jewish Revolt

The revolt against Rome began in 66 AD as resistance to heavy taxation, religious tensions, and corrupt Roman governance boiled over. Jewish zealots seized control of Jerusalem, expelled Roman officials, and declared independence. The Roman response was swift and merciless. Vespasian began a systematic campaign in Judea, and when he was proclaimed emperor in 69 AD, his son Titus took command of the final assault on the capital.

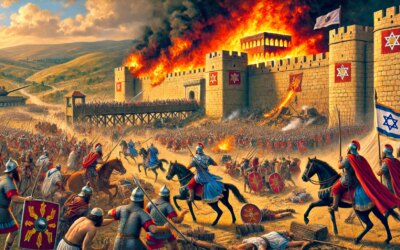

Jerusalem Under Siege

Jerusalem in 70 AD was a city divided within and besieged from without. Internal Jewish factions, including the Zealots and Sicarii, fought each other even as Roman legions encircled the city. Titus commanded four legions—roughly 60,000 soldiers—and constructed massive siege works around the city, cutting off all supply routes. Famine spread. Civilians starved. Chaos reigned behind the sacred walls.

The Final Assault and the Temple’s Fall

Despite the strength of Jerusalem’s fortifications, Roman persistence prevailed. Over several weeks, Titus’ forces breached the outer walls and advanced street by street. On August 30, Roman soldiers broke into the Temple precinct. Though Titus reportedly ordered the sacred structure spared, the flames spread rapidly—whether by accident or disobedience remains debated. The Second Temple, spiritual heart of Judaism, was consumed by fire. Thousands were killed. The city was devastated.

Aftermath and Roman Triumph

The destruction of Jerusalem had immediate and lasting consequences. Jewish survivors were enslaved or scattered. Rome celebrated the victory with the construction of the Arch of Titus, still standing in the Roman Forum, depicting the looting of the Temple treasures. Vespasian and Titus held a triumph in 71 AD, parading captives and spoils through the streets of Rome. Judea became a Roman province under harsh military control.

The Jewish Diaspora and Historical Memory

The fall of Jerusalem marked the beginning of a prolonged Jewish diaspora. Rabbinic Judaism gradually replaced the Temple-centered worship, and the memory of the destruction was etched into liturgy, art, and identity. Tisha B’Av, an annual day of mourning, commemorates this loss. For centuries, the Western Wall remained a place of pilgrimage and prayer—a fragment of the past that refused to vanish.

Titus: Soldier, Politician, Emperor

Titus returned to Rome as a hero and succeeded his father as emperor in 79 AD. His brief reign was marked by compassion and crisis—managing the eruption of Vesuvius and rebuilding Rome after a major fire. Yet his reputation was forever linked to the siege of Jerusalem. Ancient sources portray him as both a capable commander and a reluctant destroyer. His actions in Judea, however, leave little room for ambiguity.

Conclusion: Fire in the Holy City

The siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD was not merely a military victory—it was an imperial statement. Under Titus, Rome crushed rebellion with ruthless efficiency, silencing a defiant people and stamping its dominance into the stone of a sacred city. Yet the flames that consumed the Temple lit the path to a new Jewish identity and a lasting sense of exile. Titus left Jerusalem in ruins, but from that ruin rose stories, traditions, and faiths that would endure longer than any empire.