Taxation as a Pillar of Power

By 150 BC, Rome was no longer just a city-state dominating central Italy—it had evolved into a burgeoning Mediterranean superpower. With territories stretching from Hispania to Asia Minor, Rome needed a way to sustain its military conquests, infrastructure, and expanding bureaucracy. Enter taxation, a system as essential as it was controversial. The taxes levied across provinces and even in the Italian heartland underpinned Roman control, enriching the state while often burdening its subjects.

The Origins of Roman Tax Policy

In the early Republic, Roman citizens were taxed based on property and wealth, primarily to fund wars. The tributum, a direct levy on citizens, was assessed through a census—a systematic count of property and population. However, as Rome expanded, it began relying less on domestic taxation and more on revenues extracted from conquered lands.

By the mid-2nd century BC, the Republic’s economic structure increasingly depended on the exploitation of provinces. Tribute from allies and conquered territories became the Republic’s financial lifeblood. This allowed Rome to reduce taxes on its own citizens, shifting the fiscal burden outward.

The Provincial Tax System

After Rome annexed Sicily in 241 BC—the first official province—a new model of taxation took shape. Each province negotiated a treaty (lex provinciae) that outlined obligations. The most common forms of tax included:

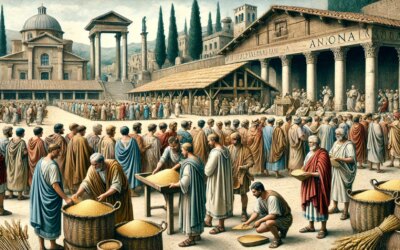

- Vectigalia: Regular taxes, including land tax (tributum soli), pasture taxes, and harbor dues.

- Decuma: A tithe (10%) on agricultural produce, particularly grain, often collected in kind.

- Stipendium: A fixed monetary tribute paid annually.

These taxes were often farmed out to publicani—private contractors who bid for the right to collect revenue. While this system enriched the Roman state and its elite class, it frequently led to abuses. Local populations were vulnerable to overtaxation and extortion, fueling resentment that sometimes erupted into rebellion.

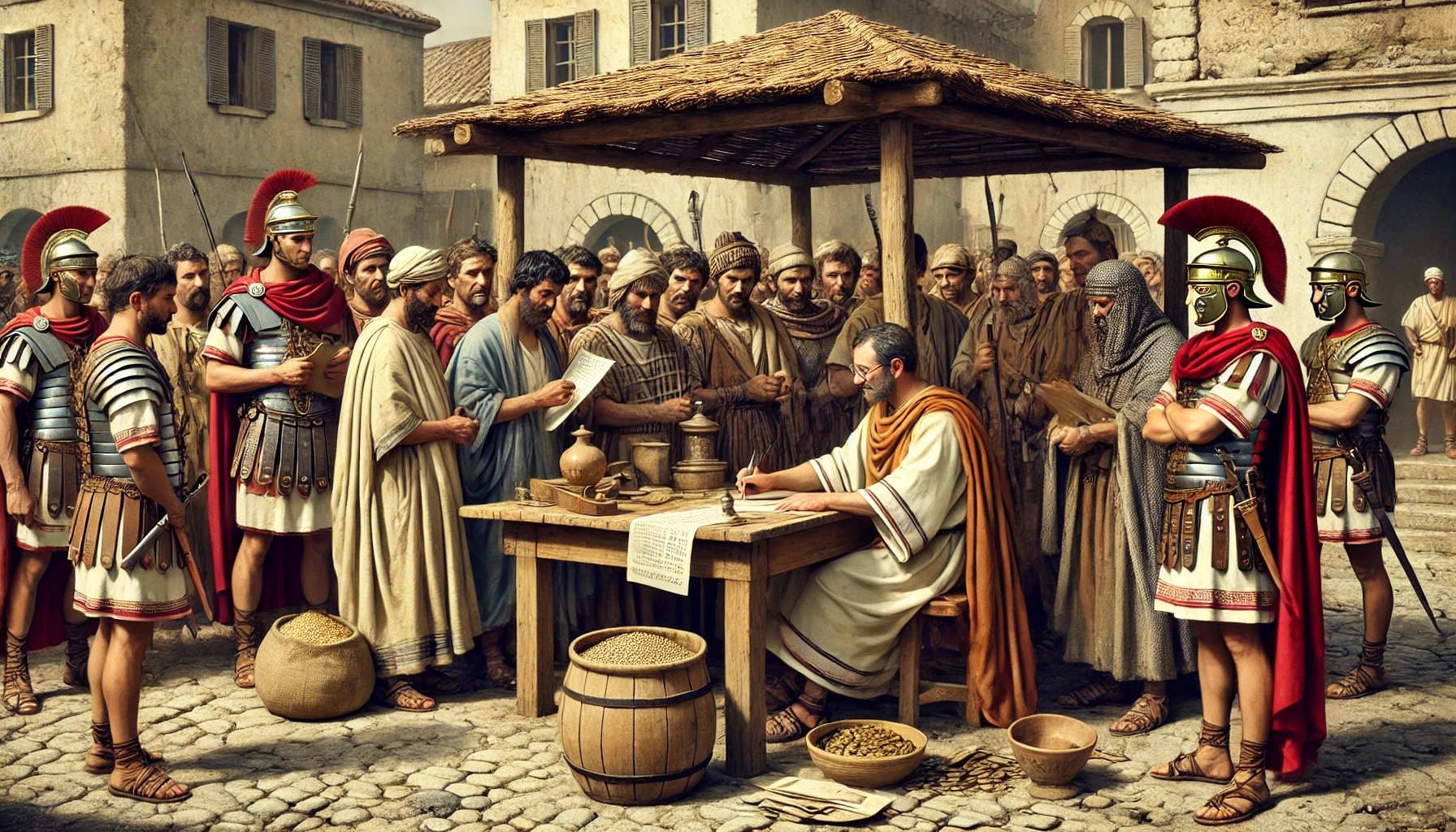

How Taxes Were Collected

In a typical provincial setting around 150 BC, a Roman magistrate, often a praetor or proconsul, oversaw tax assessments. He would be assisted by scribes, accountants, and a contingent of soldiers to enforce order. Under canopies in city forums or rural collection points, farmers, artisans, and traders queued to pay taxes—either in coinage, grain, livestock, or goods.

The scene was one of tension and necessity. Roman scribes carefully recorded entries on wax tablets. Grain was measured in standard amphorae; livestock branded for state use. Coins were weighed and scrutinized. For many locals, taxation was not just a fiscal burden—it was a visible symbol of subjugation to Roman power.

Tax Farming and Corruption

The publicani played a critical but controversial role. These tax farmers paid the state in advance for the right to collect taxes in a province, then turned a profit by demanding more from the populace. Though technically regulated, oversight was often lax, especially in distant regions like Hispania or Asia.

Corruption and abuse by publicani became so endemic that it was a key concern of reformers like the Gracchi brothers in the late 2nd century BC. The system served Rome’s elites well but came at a high social cost—many provincial cities suffered economically under crushing levies.

Revenue in Action: Funding Empire

The taxes collected fueled Rome’s military machine. They paid for legionary salaries, road construction, port maintenance, and the growing administrative apparatus. Grain collected as tax often fed troops stationed abroad or was redistributed during emergencies.

Tax revenues also filled the Roman treasury—aerarium—and enabled ambitious public works back in Rome. Temples, aqueducts, and forums were built with wealth extracted from the provinces. The spoils of empire funded its capital’s magnificence.

Social Impact and Resistance

Though taxation allowed Rome to flourish, its inequities sowed seeds of unrest. Discontent among provincials was not uncommon. In Hispania, repeated revolts were partially fueled by tax exploitation. Even within Italy, citizens complained of unfair land valuations and tax favoritism.

Resistance took many forms: evasion, bribery, appeals to sympathetic magistrates, and at times, outright rebellion. The tension between fiscal extraction and local autonomy remained a persistent challenge for the Republic and, later, the Empire.

The Road to Reform

By the late Republic, criticism of the tax system was mounting. Reformers like Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus pushed for land redistribution and oversight of the publicani. Though their efforts met violent ends, the issues they raised endured—and so did the taxation structures that Rome had refined since 150 BC.

In many ways, the Roman Republic’s ability to tax effectively was a cornerstone of its dominance. Yet the methods it employed reveal the costs of empire—not only in terms of finances, but in justice and stability. Today, as we study Roman stones and structures, we must also remember the invisible architecture that sustained it: taxation, tribute, and the will to enforce them.