Introduction: An Empire’s Edge

In the winter of 370 AD, the western frontier of the Roman Empire braced against mounting pressure. At its helm stood Valentinian I, a hardened soldier-emperor and one of the last rulers who truly grasped both sword and state. Touring the Rhine defenses, Valentinian confronted not just Germanic incursions, but the unraveling fabric of a frontier system once held by Caesar and Augustus. His mission was to hold the line—stone by stone, soldier by soldier.

Valentinian I: Soldier, Strategist, Sovereign

Valentinian I had risen through the ranks of the Roman military during a time of intense instability. Appointed emperor in 364 AD following the death of Jovian, he split power with his brother Valens in the East and retained control of the Western Empire. Fiercely devoted to military affairs, Valentinian prioritized fortification over political maneuvering, channeling imperial resources into strengthening Rome’s external borders.

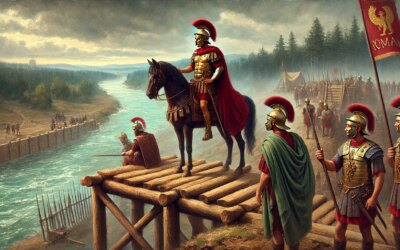

The Strategic Importance of the Rhine

The Rhine River marked a crucial boundary between Roman Gaul and the restless Germanic tribes beyond. For centuries, this natural barrier had been reinforced with forts, watchtowers, and legions. But by the late 4th century, increasing pressure from the Alemanni and other tribal confederations, coupled with internal decay, had weakened these defenses. Valentinian sought to reestablish Roman dominance through a program of restoration and expansion.

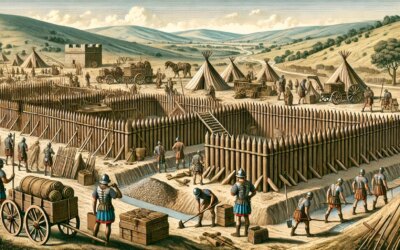

Inspecting and Reinforcing the Limes

Valentinian personally inspected the frontier, a rare act for a late Roman emperor. His visits included sites like Mogontiacum (Mainz), Augusta Treverorum (Trier), and Colonia Agrippina (Cologne). He ordered the rebuilding of crumbling walls, the construction of new forts, and the deployment of elite units along the Rhine. His engineers innovated with ditches, stone barriers, and mobile wooden towers to adapt to new forms of warfare. This was a far cry from the solid limes of earlier centuries, but it was effective—flexible, strategic, and rooted in lived threat.

Confronting the Alemanni

In 368–370, the Alemanni crossed the frozen Rhine in large numbers. Valentinian led a successful campaign to repel them, culminating in a decisive battle near Solicinium. His leadership, both from the field and the headquarters at Trier, demonstrated the potency of a hands-on emperor. Yet these victories were temporary; new waves of migrants and raiders were already forming along the Danube and in the East.

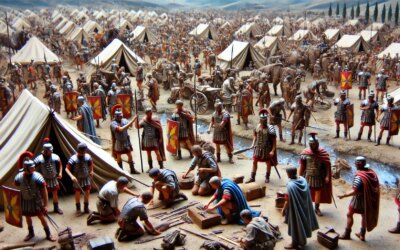

Administration and Recruitment

To support the defenses, Valentinian reformed recruitment practices, extending service incentives and accepting more foederati—barbarian allies settled within the empire under oath. He also empowered local officials, sometimes at the cost of senatorial authority, to ensure faster response times. Though sometimes ruthless, these measures reflected his commitment to preserving the western provinces from collapse.

The Sudden End of an Iron Reign

In 375 AD, during an embassy with Quadi envoys, Valentinian suffered a fatal stroke—reportedly triggered by an explosive outburst of rage. His death left the West in turmoil. The empire was inherited by his young son Gratian, but the pressure on the frontiers never relented. The Rhine, despite Valentinian’s efforts, would eventually be overrun during the great migrations of the early 5th century.

Conclusion: Holding the Line One Last Time

Valentinian I’s inspection of the Rhine in 370 AD was more than a military review—it was a desperate stand against a rising tide. His legacy is one of vigilance and determination, a reminder that even in its twilight, Rome could still find strength in the discipline of its soldiers and the resolve of its leaders. While the empire’s walls would eventually crumble, Valentinian’s example endures as the last gasp of Roman resilience in the West.