Introduction: Rome Reimagined

In 72 AD, amid the ashes of a brutal civil war, the newly crowned Emperor Vespasian made a defining gesture—not with a sword, but with stone. On the site of Nero’s private lake, he laid the foundations for what would become the Flavian Amphitheatre, known to us as the Colosseum. It was a political act, an architectural marvel, and a gift to the Roman people. This monument would transform the very center of the city and its civic identity.

Vespasian: From General to Builder

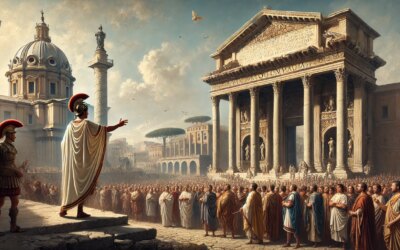

Vespasian came to power after the chaotic Year of the Four Emperors (69 AD), following the downfall of Nero and a succession of short-lived rulers. A seasoned general with humble roots, he promised stability, frugality, and a return to traditional Roman values. The decision to construct a massive public amphitheater—on land previously used for Nero’s Golden House—signaled a sharp break from imperial excess and a shift toward populist governance.

The Site: From Palace to Public Space

The location of the Colosseum was highly symbolic. Nero had built an artificial lake as part of his opulent palace complex, excluding the people from the heart of their own city. Vespasian ordered it drained and filled. The new amphitheater would be a monument not to one man’s vanity, but to the collective joy and identity of the Roman populace. This act of urban reclamation was as political as it was architectural.

The Ambition of Construction

Construction began in 72 AD under Vespasian and continued under his sons Titus and Domitian. Built largely with stone, concrete, and travertine, the Colosseum would eventually hold up to 80,000 spectators. Roman engineers employed advanced techniques, including vaulted corridors, retractable awnings (velaria), and a subterranean hypogeum to stage animals and gladiators. The project mobilized thousands of laborers, including enslaved peoples captured during the Jewish War.

Politics Through Architecture

By building the Colosseum, Vespasian projected imperial strength, piety, and humility. He funded the construction with spoils from the Judean campaign, linking military conquest with civic generosity. Inscriptions boasted of the emperor’s gifts to the people. Where Nero had built for himself, Vespasian built for Rome. The amphitheater’s enduring nickname—Colosseum—derived not from its size alone but from its proximity to the Colossus of Nero, now repurposed as a statue of Sol, Rome’s guardian sun god.

The Flavian Legacy

Though Vespasian died in 79 AD before its completion, the Colosseum was inaugurated in 80 AD by his son Titus with 100 days of games. Gladiatorial combat, wild beast hunts, and naval spectacles enthralled the masses. Domitian later expanded the structure, adding the hypogeum and upper tiers. The Flavian dynasty secured its place in public memory not through conquest alone, but through stone and spectacle—monuments that declared “Rome is yours.”

Enduring Symbol of Empire

The Colosseum outlived the empire itself. It stood as a symbol of Roman engineering, civic ritual, and the complex dialogue between ruler and ruled. Though damaged by earthquakes and stripped for building materials in later centuries, it remains an icon of Roman grandeur and resilience. Modern visitors walk the same corridors once crowded with citizens from every corner of the empire—rich, poor, free, enslaved—all watching the drama of Rome unfold in sand and blood.

Conclusion: Building Unity in Stone

In 72 AD, Vespasian took a bold step toward restoring Rome’s fractured soul. The Colosseum was more than an amphitheater—it was an act of healing, a testament to shared experience, and a redefinition of imperial identity. Vespasian ruled as a builder, not a destroyer. His greatest legacy was not merely what he conquered, but what he constructed—a stage upon which Rome remembered itself, and still does.