Welcome to the Popina

The scent of roasted chickpeas, garlic, and spiced wine drifts through a dimly lit alley. Laughter and music beckon from a low stone doorway. Inside, oil lamps flicker against painted walls as Romans gather around wooden tables, hunched over bowls of stew and goblets of wine. This is the popina—the Roman tavern. In the 1st century AD, establishments like these were not just eateries—they were the social hubs of the urban underclass and the pulse of Rome’s neighborhoods.

The Roman Tavern Defined

Popinae were simple taverns found in nearly every Roman town and city. They served food, wine, and conversation to a wide clientele—laborers, freedmen, traders, travelers, and the occasional aristocrat slumming it for fun. These spots offered more than sustenance: they provided warmth, gossip, companionship, and even illicit pleasures.

Unlike the elite dining rooms of patrician villas, the popina was casual, noisy, and intimate. It was the tavern of the people—a place where social boundaries softened and Roman daily life revealed its most candid side.

The Setting and Atmosphere

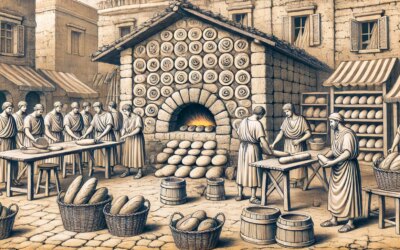

Most popinae occupied street-facing corners or ground floors of apartment blocks. Their typical layout included:

- Stone counters with embedded dolia (large jars) for wine and food storage

- Simple wooden tables and benches for communal eating

- Oil lamps and wall frescoes depicting mythological or comedic scenes

- Back kitchens with clay ovens, grills, and ceramic cookware

Amphorae of wine lined the walls. Barmaids or owners served customers, who could bring their own food or purchase hot meals. Common fare included lentils, bread, cheese, olives, sausages, and stews—all easy to prepare and consume.

The Popina Clientele

Popinae were frequented by Rome’s lower and middle classes: artisans, merchants, sailors, freedmen, slaves, and prostitutes. These establishments gave voice to those outside the Senate and equestrian orders. For many, the popina was a second home—where they could relax after work, argue about races at the Circus Maximus, or debate the latest edicts.

While elite Romans sometimes looked down on taverns—Cicero once derided them as dens of vice—some senators and wealthy youth still found their way into them, especially in disguise or under cover of night.

Wine and Entertainment

Wine was the lifeblood of the popina. Served warm or spiced, cut with water or vinegar, it flowed freely in clay cups. Stronger varieties came with higher prices and were often labeled on the shop walls. Wine lists included:

- Falernian: strong and prestigious

- Caecuban: full-bodied and sweet

- Mulsum: wine mixed with honey

Entertainment varied. Wandering musicians played flutes or lyres. Dice games and gambling were popular pastimes, and even rudimentary board games like ludus latrunculorum (a Roman version of checkers or chess) graced the tables. In some taverns, flirtation and more personal services were part of the experience.

Popinae in Roman Law and Literature

Roman law took a dim view of popinae, especially those suspected of promoting immorality. They were sometimes subject to curfews, inspections, and moral legislation. Yet they thrived—Pompeii alone had over 100 identified taverns before its burial in 79 AD.

Writers like Petronius, Martial, and Juvenal described taverns in vivid detail—often humorously, sometimes scandalously. These descriptions paint a picture of a vibrant, earthy social world removed from the decorum of elite banquets.

Women and the Popina

While elite Roman women rarely entered taverns, lower-class and working women were a visible presence. They served food, played music, owned or co-managed shops, or socialized there. In some cases, the line between hostess and courtesan was intentionally blurred, contributing to the popina’s reputation for looseness and fun.

Food, Class, and Community

In a city where most residents lived in cramped insulae (apartment buildings) with no private kitchens, popinae were essential. They offered affordable meals, warmth, and social cohesion. Patrons formed regular groups, celebrated festivals, and shared the rhythms of urban life.

For historians, popinae provide a lens into how ordinary Romans lived, ate, and socialized—outside of temples, fora, and palaces. The graffiti and murals found in Pompeii’s taverns remain some of our most candid records of ancient humor, desire, and daily chatter.

Legacy of the Roman Popina

The Roman popina laid the groundwork for later European taverns, inns, and public houses. Its blend of food, drink, and informal interaction foreshadowed the rise of cafés, pubs, and wine bars as centers of culture and dissent. Today, echoes of the popina live on wherever people gather over food and conversation in shared space.

From Stone Counters to Cultural Anchors

Whether roasting lentils or pouring mulsum, the Roman tavern keeper did more than serve meals—he (or she) cultivated community. And for the countless voices that history often overlooks, the popina offered a rare space to be heard. In every clink of a goblet and burst of laughter, we find the heartbeat of an empire—not in marble and conquest, but in the warmth of shared bread and wine.